As nations commit to and implement initiatives to transition to a low-carbon future, there is a growing demand for critical metals. A vast amount, much more than needed to meet metal demands, of four critical metals (nickel, copper, cobalt, manganese) are found in potato-sized rocks, called nodules, in the deep sea. As you might imagine, in order to access this resource, permits are required, and since this is an ocean resource, there is a complex regulatory regime. To understand the current deep sea mining regulations, it is important to acknowledge the influence of terrestrial mining and the history of how ocean jurisdictions were determined.

The Phases of Mining

Mining is a complex industry that involves three distinct phases: prospecting, exploration and exploitation. Prospecting is the phase of looking for the minerals deposits. Exploration is the process of identifying potential mineral deposits and evaluating their economic viability and the potential impacts of mining, while exploitation is the production process of extracting minerals from a known deposit.

Deep sea mining regulations are complex and are still being developed in most relevant jurisdictions. Similar to land-based mining, both the exploration and exploitation phases are/will be highly regulated, with required stakeholder engagement at key milestones.

Exploration Phase (not allowed to sell the minerals recovered)

For deep sea mining, the exploration phase takes 3 to 15 years, and the typical cost is tens of millions of dollars, and stakeholder consultation is required at key milestones. The steps in this stage are:

- Geological mapping and resource estimation, including assaying samples to determine mineral content and applying models to estimate the total resource

- Mining plan, including engineering and economic modeling of possible mineral extraction

- Environmental baseline of the area impacted by the proposed mineral extraction

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the possible mineral extraction, which includes assessing the environmental, social, and economic impact of mining, as compared to the baseline conditions.

Moving From Exploration To Mineral Harvesting

At the end of exploration, an exploration license holder may apply for a license to recover the nodules commercially. The EIA creates the core of the mineral exploitation permit application as the primary means for the regulator to assess the application.

Exploitation Phase (Commercial operations of the mine)

If an exploitation permit is granted for deep sea mining, it’s anticipated that mining under a permit would be carried out under a 15- to 30-year lease. The average estimated costs for deep sea mining infrastructure and operations is hundreds of millions of dollars. The exploitation phase for deep sea mining is likely to follow the same general process as land-based mines:

- Construction (equipment and vessels)

- Commercial production phase

- Regular monitoring and reporting requirements (typically annual unless there is a reportable incident), outcomes of which can be applied to adaptive management strategies

- Stakeholder engagement/consultation may be a requirement or common practice during production.

- Taxes, royalties, etc., are paid on a regular schedule throughout the mine’s lifespan

- Closure (mining operations cease)

- Post-closure monitoring and reporting activities

Jurisdictions

All deep sea mining jurisdictions fall under two internationally and legally defined types:

- A nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

- High Seas known as the ‘Area’ beyond national jurisdiction

An EEZ, as prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), is an area of the sea in which a sovereign state has exclusive rights regarding the exploration and use of marine resources. An EEZ is typically 200 nautical miles (230 miles) from the coast of the sovereign state in question. The exception to this rule occurs when EEZs overlap; that is, sovereign state coastal baselines are less than 400 nautical miles apart. When an overlap occurs, it is up to the states to delineate the actual maritime boundary. States also have rights to the seabed of what is called the continental shelf up to 350 nautical miles (648 km) from the coastal baseline beyond the exclusive economic zones.

With a sovereign state which has an EEZ, the government of the country decides how to regulate deep sea mining. For example:

- Reuse existing land-based mining regulations – e.g. Mexico

- Reuse existing offshore oil and gas regulations – e.g. Norway

- Create new deep sea mining regulations – e.g. Cook Islands

- Currently not allowing deep sea mining – e.g. Costa Rica

The high seas ‘Area’ regulations are set by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which is a Kingston, Jamaica-based intergovernmental body of 167 member states and the European Union established under the 1982 UNCLOS and its 1994 Agreement on Implementation. All sovereign states that are parties to the UNCLOS are automatically members of ISA. 93% of the world’s population is represented at the ISA, with the notable exception of the United States.

The ISA’s dual mission is to:

- Authorize and control the development of mineral-related operations in the international seabed, which is considered the “common heritage of all mankind.”

- To protect the ecosystem of the seabed, ocean floor, and subsoil in “The Area” beyond national jurisdiction. Additionally, the ISA is to safeguard the international deep sea, the waters below 200 meters.

The Authority operates as an autonomous international organization with its own

- Assembly (167 member states + EU)

- Council (36 members elected by the Assembly)

- Secretariat (elected by the Assembly to serve a four-year term as the ISA’s chief administrative officer, oversee Authority staff, and issues an annual report to the Assembly.)

- Advisory bodies: 41-member Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) and 15-member Finance Committee

Mature Regulatory Frameworks for Deep Sea Mining

| Size of total area (million km2) | Legal Framework (Likely) | Regulatory Body | |

| International (UN) | 194.9 | 1994 | ISA |

| USA EEZ | 11.3 | 1980 | BOEM |

| Cook Islands EEZ | 1.96 | 2009 | SBMA |

| New Zealand EEZ | 4.3 | 2012 | EPA |

| Norway EEZ | 2.38 | 2019 | NPD |

| Japan EEZ | 4.48 | 2026 | TBD |

| India EEZ | 2.3 | 2023 | TBD |

| Mexico EEZ | 3.3 | Land-based rules | Ministry for Mining |

| Sweden EEZ | 0.16 | TBD | TBD |

| Saudi Arabia EEZ | 0.19 | TBD | TBD |

| Brazil EEZ | 3.8 | TBD | TBD |

| Papua New Guinea EEZ | 2.7 | Land-based rules | Ministry for Mining |

Now, let’s dive into the three of the most active jurisdictions of over a dozen countries in different stages of deep sea mining regulations, as highlighted in the table above.

The ‘Area’ as Regulated by the ISA

The Exploration regulations status of the high seas:

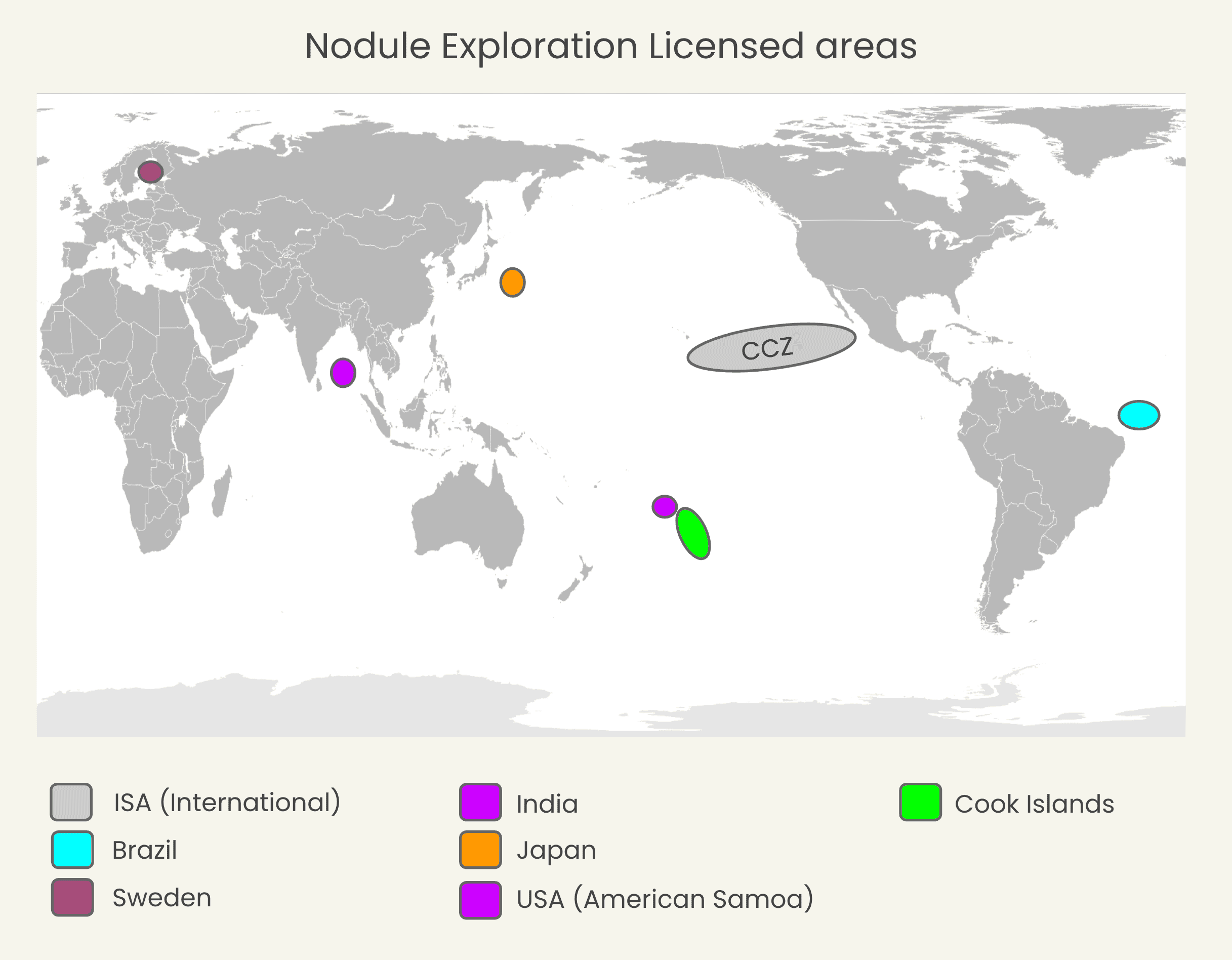

- ISA has entered into thirty-one 15-year contracts for the exploration of polymetallic nodules (PMN), polymetallic sulfides (PMS), and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts (CFC) in the deep seabed with 22 contractors.

- Nineteen of them are expiration contracts for polymetallic nodules (PMN), which are permits issued by a government or the ISA. Eighteen of those are in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), and one is in the Indian Ocean.

The Exploitation regulations status of the high seas:

- 2015 ISA circulates 1st draft of the Mining Code

- 2017 ISA circulates 2nd draft of the Mining Code

- 2018 ISA circulates 3rd draft of the Mining Code

- 2019 ISA circulates 4th draft of the Mining Code

- 2023 Roadmap date set in Q3 2024 for ISA to finish exploitation regulations

- ⅔ super majority of the assembly is required to NOT adopt regulations from the LTC advisory body.

- The Metals Company (TMC) has said they intend to submit an exploitation application in 4Q2024.

- TMC initial commercial production in early 2025, assuming the exploitation application is approved

The ISA current version of mining regulations Draft standard and guidelines for the environmental impact assessment process ISBA/27/C/4, states that:

-

- Best Environmental Practices are defined in the Exploitation Regulations• Use of best available techniques;

which is cross-referenced with the ISA current version of Draft Regulations On Exploitation Of Mineral Resources In The Area – SBA/25/C/WP.1 which defines Best Available Techniques as:

“…means the latest stage of development, and state-of-the-art processes, of facilities or of methods of operation that indicate the practical suitability of a particular measure for the prevention, reduction and control of pollution and the protection of the Marine Environment from the harmful effects of Exploitation activities, taking into account the guidance set out in the applicable Guidelines.”

The United States EEZ

The United States holds the largest EEZ worldwide when considering its numerous minority islands. It encompasses 11.3 million square km (4.3 sq miles) of ocean and is larger than the land area of all 50 states combined. Governed by the 1980 Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act and subsequent updates, the Bureau of Ocean Management (BOEM) serves as the country’s regulatory body for deep-sea mining operations.

Key regions like the Blake Plateau (located in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, off the southeastern United States coasts of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida), Hawaii, and the surrounding minority islands in the Pacific are known or anticipated to host polymetallic nodules, positioning the US as a prominent contender in the evolving landscape of deep-sea mining regulations.

Under §1419. Protection of the environment, The 1980 Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act also includes the “best available technologies” language:

(b) Terms, conditions, and restrictions

Each license and permit issued under this subchapter shall contain such terms, conditions, and restrictions, established by the Administrator, which prescribe the actions the licensee or permittee shall take in the conduct of exploration and commercial recovery activities to assure protection of the environment. The Administrator shall require in all activities under new permits, and wherever practicable in activities under existing permits, the use of the best available technologies for the protection of safety, health, and the environment wherever such activities would have a significant effect on safety, health, or the environment…”

The Cook Islands EEZ

The 2009 Seabed Minerals Act established the Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA) as the Cook Islands regulator for deep sea minerals with the Cooks Islands EEZ.

- Issued exploration regulations in 2020

- Three exploration permits were awarded in 2022:

- CIC Ltd (Consortium of companies)

- Cobalt Seabed Resources Limited (JV Cook islands Investment and GSR)

- Moana Minerals Limited (Ocean Minerals)

- Exploitation regulations are in development

The Seabed Minerals (Mining) Regulations 2020 under Schedule 9 Prescribed evaluation criteria for the purposes of section 68(1)(a) of the Act, includes the “best available technology and techniques” terminology:

(4) Technical competence: whether the applicant has the technical resources, and access to appropriate technical advice, to carry out the proposed regulated activity, and to economically extract the seabed minerals, in particular,—

(g) capability and capacity to utilize and apply best available technology and techniques.

Conclusion

Given that over a dozen jurisdictions are working to finalize deep sea mining regulations, there is a very high likelihood that seabed mining permits will be issued within the next 5 years.

At Impossible Metals, we anticipate that our selective harvesting technology will represent the best available technique, as none of the other technologies or techniques can match these environmentally low-impact features:

- The collection vehicle hovers over the seafloor, avoiding sediment disruption of landing and driving.

- Nodules are picked individually by robotic arms, minimizing sediment disruption from nodule harvesting.

- System avoids megafauna and can leave behind a percentage and pattern of nodules.

As we progress with the development of our Eureka AUV selective harvesting system, we will employ scientists to quantify our environmental impact, and we are confident that our system will have the lowest environmental impact in the industry.