Critical metals—such as copper, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and rare earth elements (REE)—are foundational to 21st-century technologies, including electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, semiconductors, AI data centers, and defense applications. ‘Winning’ the supply chain means achieving strategic autonomy, reducing vulnerabilities to geopolitical coercion (particularly from China’s dominant position, controlling the majority of global processing and mining of many key minerals), and ensuring reliable, affordable access to support innovation and economic growth. This requires a multifaceted approach combining policy, investment, diplomacy, and technology.

What are the criteria that define ‘winning’ critical metal supply chains?

Not Controlled by China

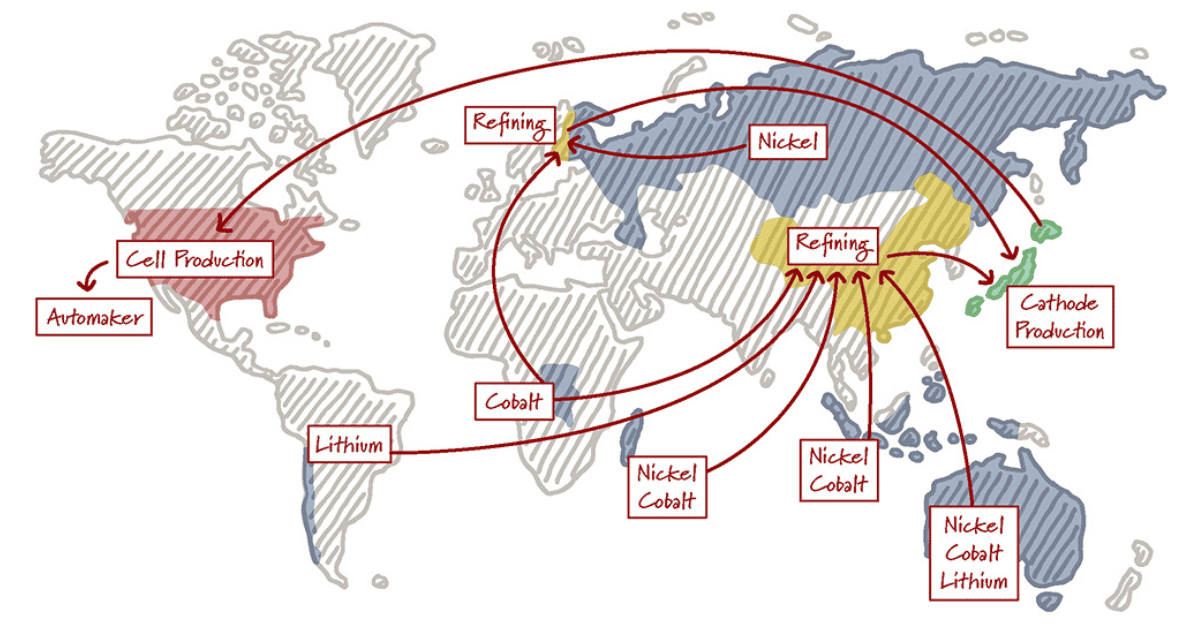

China owns and operates the majority of land-based mining and mineral processing facilities worldwide. e.g., nickel mining and processing in Indonesia, and cobalt mining in Africa. We should prioritize domestic and local mineral resources and mineral processing facilities. We should also encourage “friendshoring” with aligned countries. E.g., Canada and Australia. The big challenge with both domestic and friendshoring is the other winning criteria, especially costs and timescales.

Cost to Mine and Process

A new bipartisan investigation from the Congress Select Committee on China shows how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) manipulates global mineral prices to maintain its dominance. We cannot outspend China. If the federal government is providing funding, it should be for mineral assets at the low end of the cost curve, which are only a few years from production, and will provide the maximum protection against China’s price manipulation.

High-grade mineral resources that contain multiple critical metals and require low-cost infrastructure to access the mine location are always in the lowest quarter of the cost curve. We also need to leverage innovation in both mining and mineral processing to further reduce costs by using robotics and AI whenever feasible.

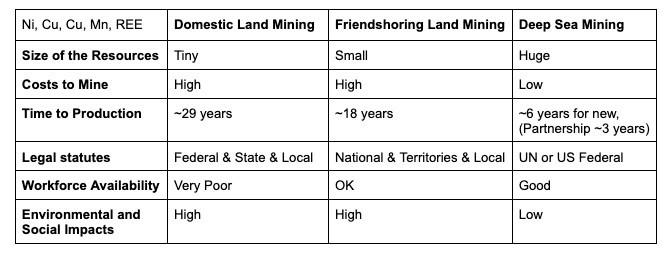

Time for Mine to Start Production

The average lead time for mines continues to rise, reaching 18 years for those that became operational between 2020 and 2024. In the US, the domestic mine average lead time is now 29 years. Permitting reform will help, but the biggest problem is the amount of litigation. Not in my back yard (NIMBY) opposition creates significant resistance, resulting in 90% more detail now required in an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to ward off litigation rather than to inform environmental decisions. This, combined with overlapping federal, state, and local statutes and the primary National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), results in massive delays.

Ideally, we need a mineral resource located in an area with no population, that does not require new transportation infrastructure (E.g., roads and rail), and that is covered by a single legal statute.

Workforce Availability

The number of mining engineering graduates in the US has significantly declined. Reports from 2023 indicate approximately 162 bachelor’s graduates, a fraction of the demand, while China graduates 3,000+ mining engineers annually, highlighting a significant global shortage. Many existing mining engineers are approaching retirement age, resulting in a shrinking pool of engineers.

Students in the US are less interested in mining. Enrollment in U.S. mining engineering programs has fallen sharply in recent years — by nearly 39% between 2016 and 2022 — and mining-related degree programs at American universities have also dropped significantly, reflecting reduced student interest in pursuing careers in mining. Ideally, we need a resource that does not require traditional mining engineers but can leverage non-traditional mining expertise.

Size of the Resources

High concentrations of metal ore only occur in specific locations. Most of these have been mined for many years. We need to invest in metal resources sufficient to support US mineral security for many decades to come.

Environmental and Social Impacts

As existing mines are depleted and ore grades decline, we are forced to mine in more remote locations and remove vastly more ore. These locations require additional transportation infrastructure and often have the highest living biomass. E.g, nickel rainforests in Indonesia or cobalt rainforests in Africa. Often, these locations have Indigenous people heavily impacted by the new mine.

Ideally, we would mine in locations with no people and the lowest living biomass, and use new AI technology to protect and preserve the habitat. At the same time, we only remove a small percentage of the resource.

How about Polymetallic Nodule Mining in the Deep Ocean?

We know that there is 3x more nickel, 12x more cobalt, and 5x more manganese in the ocean than in land-based reserves. There are also significant amounts of copper and rare-earth elements because 71% of our planet is ocean, and no deep sea mining has occurred to date.

Today, China holds 16% of international permits for deep sea mining, more than any other country, but that is a tiny fraction of the control China has over land-based mines, especially in Africa and Indonesia.

Polymetallic nodules contain high grades of copper, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and rare earth elements, and they lie like potatoes on the seabed surface. No blasting, cutting, or tunnelling is required. In the ocean, no new roads or railway lines need to be constructed; we simply reuse existing bulk carrier ships and ports. These factors result in nodules being, on average, twice as valuable as equivalent land-based ore and have up to 10x lower cost structure. This protects against China’s price manipulation.

There are ~$18T worth of nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) between California and Hawaii. This area has more than 16 concession areas awarded, and some concession holders have held their areas for over 20 years. Friendly nations own and have collected decades of environmental baseline data. These areas can begin production within the next few years, decades earlier than new land-based resources.

We also know that at depths of 3–4 miles and hundreds to thousands of miles from land, no humans are directly affected by mining. The amount of living biomass is orders of magnitude less than in a rainforest, with the vast majority being microscopic.

Collecting polymetallic nodules does not require traditional mining engineers, as the potato-sized rocks lie on the seabed. New technology can use hovering robotics and AI to selectively collect nodules, avoiding visible life and only collecting a small percentage of the resource.

Polymetallic nodules are not formed close to shore, so the legal regime governing them is either a national (federal) jurisdiction or an UN autonomous intergovernmental organization, which avoids jurisdictional overlap and reduces time to production.

Options for Critical Metals Ore Not Controlled by China

Conclusion

The US needs to invest in mining locations where costs are so low that the PRC can not manipulate global mineral prices to maintain its dominance. These locations should have substantial resources and be geographically close to the US to enable domestic mineral processing. In addition to investing in deep sea mining innovation, we also need to invest in domestic mineral processing and recycling. Long-term, over 30+ years, recycling will help us meet demand for critical metals.

Deep sea mining of polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, combined with new domestic mineral processing, represents the best strategy to secure the critical metal supply chain in the 21st century.

Image source: CLEARPATH