International deep-sea mining regulations—set by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and national governments with deep-sea minerals within their exclusive economic zone (EEZ)—establish the laws and guidelines controlling deep-sea mining activities. Like land-based mining, both the exploration and exploitation phases of deep-sea mining (DSM) are highly regulated, with required stakeholder engagement at critical milestones. (Learn more in this blog post about the Current Status of Deep Sea Mining Regulations.)

To date, there has been an emphasis on baseline studies, protocols for these studies, and the research papers generated by this work. Based on the argument that there is not enough data, this body of work could be interpreted by some as being in opposition to, or a counter-narrative to, “the mining company’s position” on matters. This interpretation sets up a false dichotomy—on one side is research, and on the other is the company line. This interpretation also sets up a false expectation—that society must decipher the arguments and decide which side to take in this ‘debate.’

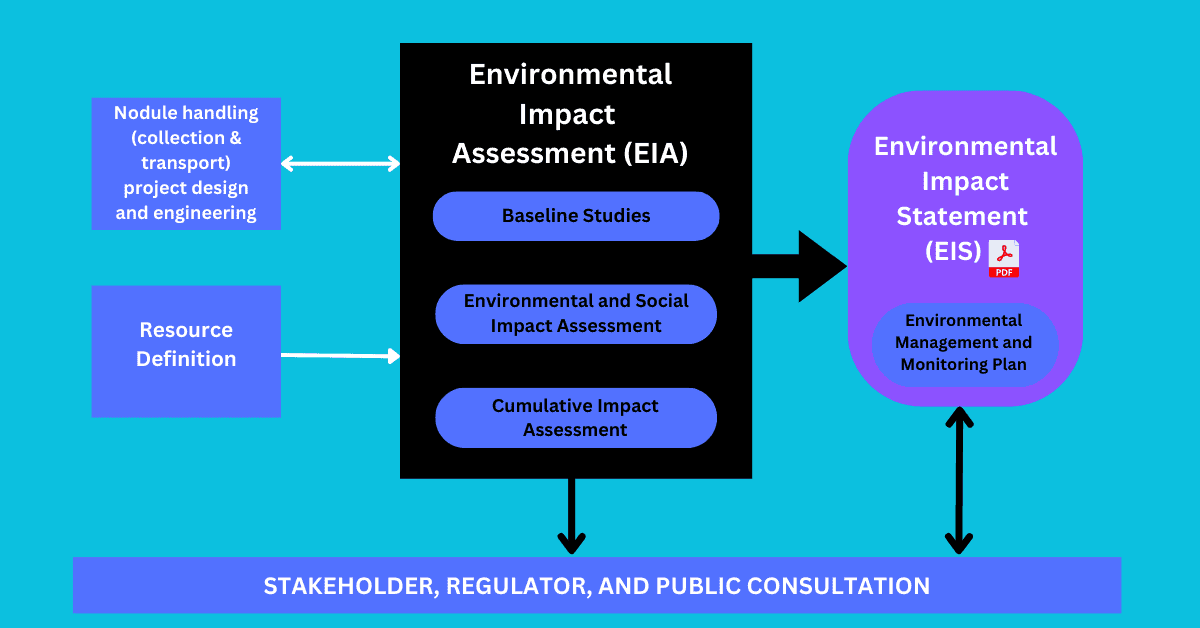

What is missing in the discussion is an appreciation of the centerpiece of the decision-making—the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), which transparently identifies the impacts.

What is an EIA?

An Environmental Impact Assessment is a typically 3–5-year process involving hundreds of people. It is a series of baseline and technical studies, modeling, and analysis that aims to understand the receiving environment, the nature, and scale of impacts, identify mitigations, consult and liaise with regulators and stakeholders, interface engineering design and mine planning with environmental risks, assess optionality and weigh various alternatives. An EIA provides a formalized and transparent impact assessment that outlines how project pressures cause effects, how those effects work individually or in concert to cause impacts, and predicts the consequences of impacts in terms of their expected magnitude and duration.

In some circumstances, it is necessary to fold the Social Impact Assessment into the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) process. The Social Impact Assessment runs as a separate parallel process in other cases.

What are Baseline Studies?

The baseline studies are multi-year investigations with two primary objectives (1) to characterize the receiving environment to understand potential impacts (2) to establish the key parameters of the pre-development baseline against which future monitoring can be compared. The scope of baseline studies is dictated by the information requirements of an EIA and typically involves research vessel deployments to collect data. The types of data collected include eDNA, water samples, seabed multicore samples, sieving boxcore mud for very small fauna, collecting megafauna, putting out bottle landers, sensors and doing high-resolution Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) and Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) surveys.

What is an EIS?

An Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is a report generated at the end of the EIA process. It is typically a multi-volume report that includes technical appendices that present the evidence associated with the technical studies and the main report chapters that describe the project and its impacts. The EIS will include an Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan (EMMP).

What is an EMMP?

The Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan is the field plan/program developed by the EIA group to explain to the regulator how the contractor (the company that holds the expiration license) will manage and monitor the impact of deep sea mining at their claim site. The EMMP will include a Closure Plan, which is how the contractor will ensure the DSM site is left in the best condition possible for future recovery after DSM is complete.

What is the Function of an EIS?

An EIS has three functions for three primary audiences:

- Regulator – The EIS provides evidence that impacts are acceptable, the development can proceed without causing serious harm, and suitable monitoring measures are in place to confirm predictions and respond if adaptation is required.

- Stakeholders/Public – The EIS transparently describes the project and the EIA process, clearly outlines the impacts (pre- and post-mitigation) and alternatives, the residual uncertainties, the monitoring to take place to validate and confirm predictions, and the management systems that will be in place to act on monitoring data.

- Proponent and Investors – The EIS communicates the proponent’s risks about environmental impacts and the obligations for monitoring and environmental performance. If the proponent has received external funding (e.g., banks, investors, etc.), this requirement extends to any downstream sustainability policies they have.

Q&A

Does a comprehensive baseline have to exhaustively measure every ecosystem component and solve every aspect of ocean science? If so, how can this be achieved in 3–5 years?

No. No single baseline for any development project can hope to solve Ocean Science and answer every question. A baseline project is not an unbounded ocean research exercise. The scope of a baseline project is defined by an EIA Scoping Study that identifies the parameters essential to assessing impacts and that directly connect to monitoring key indicators. However, there is an interface between a baseline project and regional and global ocean science objectives. By aggregating results across several individual baseline projects using consistent methods, regional assessments are made, and by integrating across information sources, the knowledge of global ocean science is improved. Publishing the objective findings of baseline studies is a key global knowledge enhancement process.

How much does it cost, and how long does it take to run the EIA program for DSM?

Collecting and analyzing the data and writing the EIS report typically take three to five years. This is the primary purpose of the exploration license. The cost is typically around $30–80M.

Do Stakeholders and the Public get a say in the EIA?

Stakeholders are engaged throughout the EIA process. EIS submission typically involves a public consultation period during which any parties can provide comments registered by the regulator and proponent and require assessment.

What else does an EIS (Environmental Impact Statement) contain?

Additional elements of an EIS include stakeholder consultation outcomes, Environmental Management and Monitoring Plans, closure plans, and adaptive management measures. An EIS typically assesses project alternatives and states the no-development case. A level of Cumulative Impact Assessment (CIA) is typically required.

If EIAs are paid for or authored by the proponent, can they be objective and trusted?

Yes. EIA is a branch of environmental science done by objective professionals with the necessary qualifications and experience. Given the oversight in modern EIA practice, project approvals do not benefit from poor quality EIAs or overt client advocacy. EIA specialists do not engage in client advocacy. Furthermore, independent reviews, panels, committees, and hearings are a standard practice in EIA.

Once an EIA is submitted, is the regulatory body forced to award an environmental permit?

No. The award of an environmental permit is contingent on a variety of factors. These include the comments from the public consultation period, independent reviews, and regulators’ internal assessment processes.

Can a contractor do whatever they want if an environmental permit is awarded?

No. The permitting process involves setting a range of conditions. Permit conditions can include a range of measures, including additional studies, revised modeling, additional monitoring requirements, etc. Regular reporting and independent monitoring are also part of the checks and balances applied.

Does approval require consensus?

No. EIS does not seek consensus among all parties, and the award of an environmental permit does not require a response to every public comment on every topic.