Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Please contact our team if you have any questions that aren’t covered here or would like to discuss your questions or feedback with Impossible Metals.

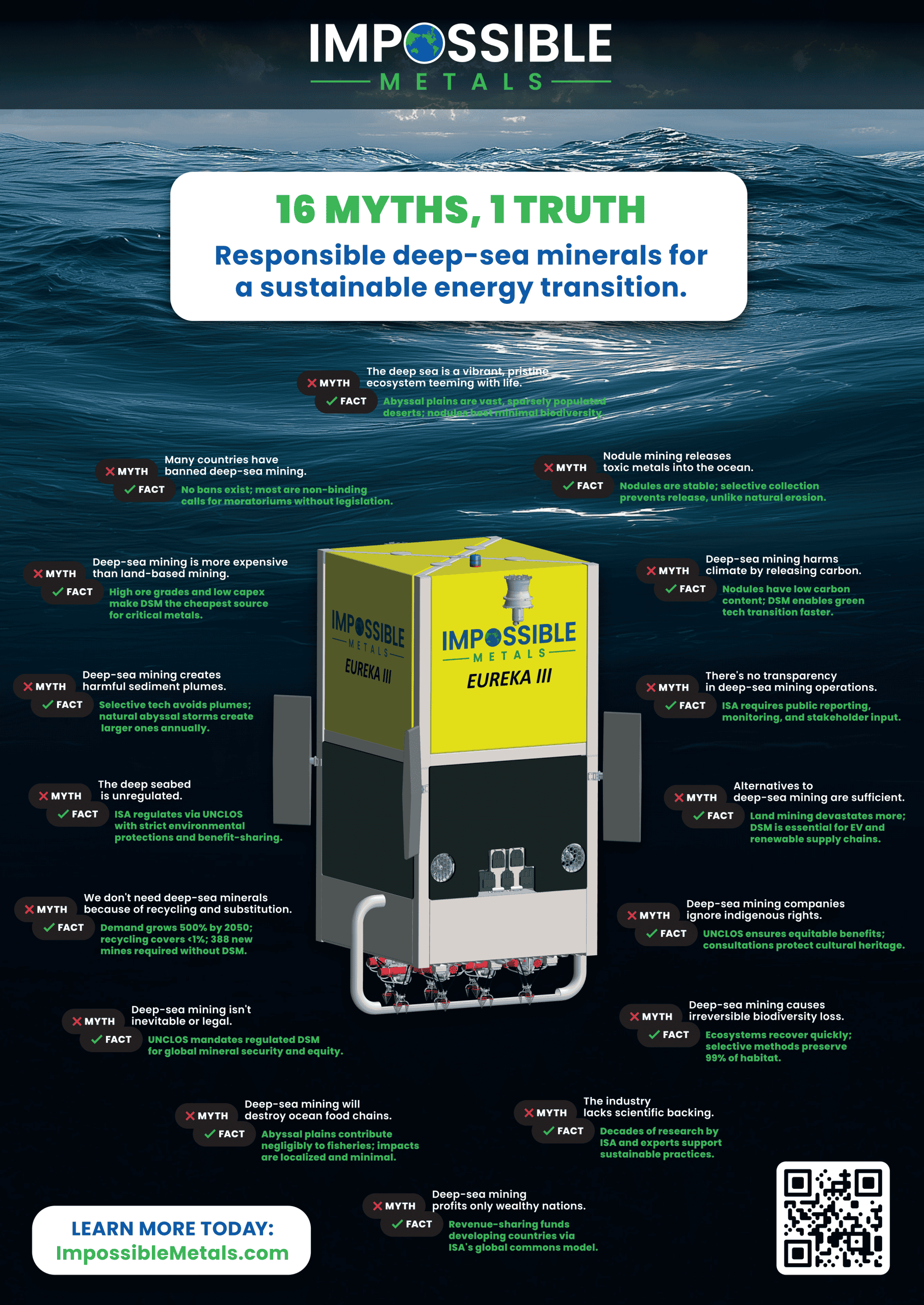

Mythbusting False and Misleading Statements About Deep Sea Mining (DSM)

Deep sea mining is an emerging industry that has sparked significant excitement, speculation, and concern. Like any emerging industry, this can lead to misconceptions or confusion, and even in some cases misleading or false statements. Impossible Metals is committed to evidence-based, environmentally responsible, and transparent operations, and therefore we have published substantial information on the expected impacts—positive and negative—of deep sea mining, and how our approach differs. However, certain myths persist and are unfortunately repeated by some organizations, particularly those with a stated goal of stopping all deep sea mining. Our planet, economy, and security requires a critical minerals policy that is based in science, and the data clearly show that selective harvesting of seabed minerals will be the lowest cost, lowest environmental impact, and lowest time path to a secure critical minerals supply chain. In the past, a number of well-meaning organizations opposed nuclear power, and we lost 20 years of innovation in a technology that is now recognized as critical to producing clean, reliable, baseload energy.

This section of our extensive FAQ will address common myths on deep sea mining. We have had productive dialogues and exchanges with the majority of the non-government organisations (NGOs) and marine scientists engaged in deep sea mining issues, and welcome other organizations to engage with us to strengthen the scientific foundation of this new industry. Regardless of the source, we take feedback constructively in line with our value of encouraging sharing and respecting all perspectives.

Impossible Metals commits that we will only mine if we are satisfied that our Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) show there will be no material, long-lasting impacts on the marine habitat or other uses of the ocean. (fishing, transportation, recreation, submarine cables, etc.)

It is an ‘old saw’ that we know less about the deep sea than the moon. While that may have been true in 1969, the last few decades have seen tremendous amounts of data collection and scientific research on the environmental conditions of the sea floor—much of it enabled by the interest in seabed mining.

The comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) studies conducted within a specific mining area for planned mining operations provide a detailed understanding of the environment, enabling us to predict potential impacts and subsequently inform regulators’ decisions on whether to issue exploitation permits. Several have been already completed in licensed areas of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, for example.

As there has been exploration activities in the deep sea and abyssal plains for decades, there is actually a tremendous amount of raw data. The problem is that there has been limited funding to process and structure this data — and substantial funding only will become available when commercial activity is permitted.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) DeepData Database contains data collected from mining contractors since the early 2000s. At the time of writing, this includes:

- Number of scientific cruises: 148

- Total Samples: 759,628

- Total Bio Samples: 150,920

- Total Geo Samples: 608,708

Globally, several programs are combining data to provide a better understanding of our oceans.

- Seabed 2030 aims to map the entire ocean floor by 2030.

- The World Ocean Database hosts the world’s largest database of data about the ocean water column (temperature, salinity, oxygen, nutrients, etc., by location & depth).

- The Ocean Biodiversity System hosts open-access data on marine biodiversity, connecting 500 institutions from 56 countries.

For more details, see our blog post: Data from the Deep Seabed: What Do We Know?

Some have argued that because the ocean is the largest carbon reservoir on Earth, holding significantly more carbon than the atmosphere or terrestrial biosphere, deep sea mining would release carbon.

However, the reality is that less than 1% of the CO2 sequestered in the ocean’s upper layers reaches the deep sea floor annually. As the carbon-based organic matter sinks to the bottom of the ocean, much of it is processed before reaching the ocean floor. Due to lower productivity and reduced input of organic matter, deep-sea sediments have an overall low organic carbon content of approximately 0.05% of the dry weight of the sediment. Nodules do not sequester CO2 and do not contain a meaningful amount of carbon. Sediment disturbed by the collector vehicle has no pathway to the atmosphere. Local sediment disturbance has shown not to rise more than a few meters, many meters away from phytoplankton, which need light for photosynthesis. Impossible Metals has no riser system with a mid-column discharge plume, so this will not impact phytoplankton photosynthesis.

Any possible carbon sink impacts will be confirmed by scientists as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) before permission is granted to start mining. See more details in the ISA Fact-check 2024/1 – The carbon cycle in the Area.

Often, we see images of the shallow ocean alongside calls for a moratorium on deep sea mining. The implicit message is that the deep ocean has a similar amount of life. While the lack of light or life in the deep sea makes pictures a relatively uninteresting complement to articles or fundraising appeals, this is like using a picture of the rainforest to illustrate the desert.

The deep ocean receives no sunlight, has no plant life (flora), and the vast majority of life is microscopic (e.g. bacteria). Every few kilometres or miles, megafauna (life bigger than 1cm) is present, but it is very rare. The deepest diving marine mammal is the Cuvier’s beaked whale, which can dive to a depth of nearly 3,000 meters (9,816 feet) according to Whale Scientists. This is well above depths of 4-6km (2.5 to 4 miles), where deep sea mining for nodules will occur. Our Eureka Collection System uses AI to avoid disturbing megafauna and is programmable to leave any percentage of the nodules undisturbed. The Eureka Collection System is initially set to leave 60% of the nodules undisturbed but can be adjusted to meet changing requirements.

Below are two videos of the actual seabed recorded with remotely operated vehicles (ROVs).

From the BGR (German) area of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ)

From the Moana Minerals area of the Cook Islands EEZ

Opponents of deep sea mining argue that it will damage a pristine environment in an irreversible way. This belief does not account for the impacts of existing mining sources or the opportunity to minimize mining impacts through technology.

All mining removes natural resources from a location, but it has been pursued throughout human history as an indispensable part of economic production. Historically, mining has had a profound and multifaceted impact on civilization, shaping economic growth, technological progress, and infrastructure, while also contributing to environmental degradation, social conflict, and geopolitical tensions. Without mining, there would be no civilization and no technology.

As demand for critical metals increases due to the energy transition, vital infrastructure requirements, digital transformation, and defense resilience, the question becomes: where should mining take place?

We believe it should come from places with the least amount of biomass, where the vast majority of life is microscopic, and no humans are living close to the mine. This is the ocean’s abyssal plains, which are located between 4,000 (2.5 miles) and 6,000 (4 miles) meters deep. Currently, ~75% of nickel is mined in rainforests, and 75% of cobalt mining originates from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with significant environmental and social impacts, including human rights abuses.

Technological innovation can also mitigate the impacts. Impossible Metals’ approach focuses on creating the most environmentally responsible form of mining. Far from creating irreversible damage, this approach maintains existing ecosystems—something never before achieved in mining. See FAQ B.6 What is Impossible Metals’ plan to protect the marine environment? for more information on what that entails. Deep sea mining can be the lowest-cost and lowest-impact source of critical minerals, enabling policies to stop sourcing minerals from rainforests or locations that use child labor.

Because deep sea mining involves such incredible technology, capable of operating in one of the universe’s most demanding environments, some assume that it will be economically risky. And it is true that all first-of-their-kind projects employ more risks than established industries. However, the rising demand for critical minerals and the surprisingly low costs of deep sea mining—particularly with Impossible Metals’ innovations—make it a potentially significant new industry.

The demand for critical metals is enormous and growing. In 2025, the total market for nickel, copper, cobalt, and manganese is approximately $450 billion per year, and is projected to reach $650 billion by 2030.

The cost to mine and process nickel using Impossible Metals technology is expected to be approximately 10x less expensive than the average land-based mine in 2024. For more details on why costs are so low, please see this blog post: Why Will Deep Sea Mining Be Less Expensive Than Traditional Land-Based Mining?

In our latest concept economic model (v7), we demonstrate how ‘Project 1’ will collect 6.7 million metric tonnes of nodules per year, generating $4 billion in revenue and a net profit of $1 billion per year. This is while leaving undisturbed 30% of the nodules by mass (60% by quantity, selecting the largest nodules).

A number of countries are listed as having signed up for a moratorium, pause, or ban. It primarily signifies that:

- Legal structures should be in place to properly regulate deep-sea mining and

- Deep-sea mining should only occur if it can be managed in a way that ensures effective protection of the marine environment.

These principles align with the purpose of the approval processes established by regulators such as the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and other national regulators, including the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA) and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).

A key component of the regulatory process is the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), which must be approved by the regulator before any mining can commence. The EIA documents the potential impacts of a particular mining project in a particular location, and outlines prevention and mitigation measures. Based on this assessment, the ISA determines whether the net impact is acceptable and whether mining can proceed.

The similarity in the purpose of moratoriums and approval processes gives the impression that jurisdictions are saying “no” to DSM. However, this isn’t entirely accurate. Essentially, signing onto a moratorium means supporting the completion of a robust mining code—something these countries are already doing, and a goal that Impossible Metals shares.

To date, 40 countries have adopted national legislation for deep sea mining and are listed in the ISA database. See more in our blog post: What Does It Mean to Support a Deep-Sea Mining Moratorium?

Communities with long traditions and deep economic ties to fishing are understandably concerned about potential impacts on fish. Fortunately, deep sea mining takes place miles away from fish, and has been shown to avoid impacts that could disturb fish—especially with Impossible Metals’ approach.

Fisheries stocks are not present on the deep ocean abyssal plains where we find polymetallic nodules. Local sediment disturbance has been shown not to rise more than a few meters, many kilometers (or miles) away from phytoplankton (food for fish), which need light for photosynthesis. Impossible Metals has no riser system with a midwater discharge plume, so this will not impact phytoplankton photosynthesis.

Potential fisheries impacts will be confirmed by scientists as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) before permission is granted to start mining.

See more details in the ISA Fact-check 2024/2 – Status of fishing activities in the Area.

Recently, most of Australia’s nickel mines have been placed into care and maintenance, due to low nickel prices and competition from Chinese-operated mines in Indonesia. The extra supply of Indonesian low-cost nickel caused the global prices to decrease, resulting in high-cost Australian mines becoming uneconomical.

When low-cost deep sea minerals come to market, this new supply will cause the global nickel price to decrease further. In addition to the high-cost producers, the mid-cost producers will also become uneconomical and will close. As a result, deep sea mining will start to replace terrestrial mining, although it will never replace it 100%. It will also make it very unlikely that new terrestrial mines will open.

Policy can also make a difference. In the U.S., for example, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act has made significant strides in prohibiting the importation of goods into the United States manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the People’s Republic of China. If more countries had secure domestic supplies of critical minerals, it would strengthen their ability to take similarly aggressive action against goods manufactured with minerals mined with forced labor or from rainforests.

While not every jurisdiction has completed their final regulations for full scale commercial mining, deep sea mining has been regulated for decades. No commercial seabed mining has happened yet, precisely because of these regulations, which prohibit deep sea mining without a license.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) adopted the exploration regulations for polymetallic nodules on July 13, 2000. Since then, 31 exploration licenses have been awarded. A draft set of regulations governing commercial extraction has also been under discussion at the ISA since 2011, when Fiji requested the ISA to prepare a work plan for adopting the extraction mining code, with iterative revisions released (e.g., 2015, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2024). The ISA has undoubtedly been delayed by motivated opponents hoping to stop all deep sea mining, but the issues are well understood and the ISA could finish their commercial mining regulations within a year.

Other nations, including the Cook Islands, Japan, Mexico, Norway, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, and the U.S. , have already completed exploration and/or commercial mining regulations. These regulations allow for mining in domestic Exclusive Economic Zones, generally within 322km (200 miles) of their shoreline. In the case of the U.S., domestic law also permits U.S. companies to apply for mining licenses in international waters; two such licenses were issued several decades ago and remain active.

Many coastal communities have strong cultural and historic ties to the oceans. Respecting these connections while benefiting from marine resources is something that many industries must manage, from fishing to tourism, from shipping to offshore oil and gas.

Deep sea mining activities must be respectful of cultural heritage through engagement with any and all communities that are geographically linked to the resource areas where mineral harvesting is taking place. All deep sea mining will detect tangible cultural heritage (e.g. a ship wreck) and should avoid disturbing the wreckage. The draft ISA mining code, for example, contains a section specifically devoted to regulating these issues.

Because the ecological forces that lead to the development of seabed mineral resources like polymetallic nodules only occur at depth, deep sea mining of polymetallic nodules will be a hundred or more miles (~160km) away from any land mass, at depths of between 2.5 and 4 miles (4-6km). International waters are typically thousands of miles or kilometers away from any habitable landmass.

Every day, land-based mining results in immediate and devastating consequences by displacing communities, destroying ecosystems, and violating the human rights of Indigenous peoples who have lived in harmony with these lands for generations. These impacts are direct, visible, and culturally irreparable. Deep-sea mining offers the opportunity to replace those mines with sources in distant, uninhabited parts of the ocean’s abyssal plains that lack the immediate cultural and human toll that we see on land. Protecting living cultures and human dignity must take priority. See more on the blog post: Illegal Land-Based Mining Consequences and How Deep Sea Minerals Can Help.

Some have argued that the natural sedimentation rate of the ocean is only of the order of 1-2 mm/thousand years, to imply that any sediment disturbance in the deep sea is unnatural. However, this is factually inaccurate. This number ignores benthic storms and seismic activity on the seabed floor, which significantly increase the sediment rate. Hence, we will not generate 23,000 times the rate of natural sedimentation.

The exact amount of sediment disturbance for each mining project will be confirmed by scientists as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) before permission is granted to start mining. The sedimentation rate will depend on the particular sediment composition in an individual site and the technology used, but it is established that the Eureka Collection System generates a fraction of the sediment disturbance compared to the dredging/riser technology developed by the other DSM companies.

The AI machine/computer vision is looking for three things. The seabed, nodules, and anything else. We assume anything else is life that we want to avoid disturbing. Hence, we do not need to train the AI, nor do we need to have seen life before encountering it. As there is no light at these depths, we control the illumination with our own lights, which significantly simplifies the computer vision complexity.

Some local sediment disturbance will occur when the nodule is picked. The cameras identify the location of the nodule in front of the vehicle. The nodule’s location is tracked relative to the robot through precise tracking of the vehicle position. With the nodule out of sight from the camera, because the robot’s position is precisely tracked, the nodule’s location is understood, enabling the arm to pick it up even without our system seeing it at the same time. With the nodule under the vehicle, the arm picks it, and any disturbed sediment is well behind the camera. Additionally, the vehicle will travel primarily into any existing current. Between the vehicle’s motion and the surrounding currents, any sediment distributed under the vehicle will remain behind it.

The International Energy Agency forecasts that the secondary supply of batteries and the reuse of nickel will represent just 3% of total demand in 2030 and 10% in 2040. There just is not enough material in circulation for recycling to move the needle in the next 25 years. To help close the demand gap, mining for new metals will still be essential.

Substitutions come with severe compromises, such as reduced driving range.

Without new mineral sources, the only remaining option would be a diminished economy—families having one less car or turning off the air conditioner, or denying developing countries access to economic growth and the greater carbon intensity it brings.

Groups opposed to deep sea mining heavily amplified the topic of dark oxygen based on a single paper. Other studies report conflicting results — for example, Paper Says Dark Oxygen Production Thermodynamically Impossible.

For more information, see question B.18.

The “China problem” is that China’s overwhelming dominance in mining, mineral processing, and the manufacturing of critical metals gives it the power to disrupt or control access for the rest of the world, creating dependency risks for the energy transition, AI data centers, and defense.

China holds a dominant position in the mineral processing of critical metals; however, an increasing number of countries are restricting the export of ore, requiring that mineral processing occur within their own borders. For example, a ban prohibiting all nickel ore exports took effect in 2014 in Indonesia. As a result, China has stepped up financing and control of foreign mines, resulting in 75% of Indonesia’s nickel refining/smelting capacity as of 2023.

China now controls a vast number of mines in Africa and Indonesia, not just the mineral processing.

A scientific paper shows that there are no fundamental health risks associated with the natural radioactivity of nodules. Please refer to Question B.19 for more information.